May 22nd 2005.

I know, I know. Most Celtic fans would do an all-day sesh in the Louden Tavern before we’d volunteer to relive the events of that day, which time has boiled down to the grim tabloid headline Helicopter Sunday in the collective memory. But when it is remembered, it’s as an isolated event, the scale of the calamity that befell Martin O’Neill’s side at Fir Park so vast it eclipses all other context. To win the fourth league title of the Irishman’s reign, Celtic only had to beat a Motherwell side that had nothing to play for, cobbled together from little-known youngsters and veterans with a 41-year-old Gordon Marshall in goal. They didn’t, and O’Neill’s departure was announced two days later. End of.

But that disregards the salient facts which come to light when you retrieve that season’s black box from the wreckage. Oversights and critical flaws which meant O’Neill’s beloved side – treble winners, heroes of Seville, whitewashers of Rangers, vanquishers of Juve, Barca, Lyon and so many others – had become something of a ticking time bomb by the last of those five years he spent pogoing around Celtic Park’s home dugout with socks tucked over trackies.

Two Ibrox defeats in 10 days during November. A five-point return in the Champions League group stage, not bad nowadays but poor by that era’s standards. Four home losses in the league – twice as many as any other season under O’Neill. Transfer business (Henri Camara, Juninho, Stephane Henchoz) which had become a tragic parody of the club’s former success poaching experienced heads from the Premier League. The physical and mental fatigue of yet another campaign fighting on four fronts, for a squad still heavily reliant on a core of battle-weary veterans in their 30s. Oh, and there was the loss of Henrik Larsson the summer prior, who, as it turns out, was a bit of a miss…

None of this excuses the waking nightmare that unfolded at Fir Park. But put it all together and it becomes less a question of why Celtic stumbled at the final hurdle that day, and more how they made it to the final hurdle with their ambitions intact in the first place. Red flags had been popping up throughout the campaign, yet heading into the final six days, two wins against the sides that finished 6th and 9th in the SPL was all that was required for a second league-and-cup double in 12 months and the fittingly glorious send-off O’Neill deserved. How?

The answer lies in a January deadline day deal that was equal parts desperation and inspiration. A signing so full of energy and personality he was effectively the gym instructor who knocked Celtic’s Zumba class of wheezing, creaking pensioners into shape and singlehandedly carried them for the next four months, until he and they came crashing to the ground with the finish line in sight at Fir Park. A player who deserved better than the ignominy of that afternoon, and whose failure to agree a permanent transfer that summer remains one of the most rueful ‘what if’ moments in the club’s modern history.

As a banner in the away end read before Celtic’s win at Ibrox that April: welcome to the Craig Bellamy show.

The Craig Bellamy we see nowadays, in his new role as Burnley assistant manager, as a pundit, or on podcasts (like the one where he recently outed himself as a major Ange Postecoglou fanboy, dating back to their mutual association with City Football Group) almost always comes across as thoughtful, articulate and likeable. These are not the first three words anyone in England would have chosen to describe him back in 2005. We won’t spend too long wondering what they would have been, but ‘gobshite’ would have been pretty high on the list. Perhaps unfairly, for someone who won silverware with three different clubs, had almost £50m worth of fees spent on him, represented Wales 78 times and hit a winner against Italy in front of 72,000 people, his career is largely remembered as a sort of inner-city Cardiff reproduction of Rebel Without a Cause, with Bellamy subbed in for James Dean.

The most infamous flashpoint was of course the one involving Liverpool teammate John Arne Riise, a Portuguese golf resort, karaoke and an 8-iron, but even that pales into insignificance compared to what went down towards the end of his time at Newcastle United, when the diminutive striker picked fights (sometimes verbal, sometimes physical) with manager Graeme Souness, local icon Alan Shearer, coach John Carver – pretty much everyone other than the tea ladies, actually.

This may not have been great for Bellamy’s reputation at a time when he was just 25 years old and still making his way within the game, but it was music to the ears of a certain Peter Lawwell. As late as January 29 the Welshman was said to be en route to the Midlands for talks with Steve Bruce’s Birmingham City, a £6m fee already agreed. But 48 hours later, in a plot twist that wouldn’t look out of place in Bruce’s novel Striker! (currently £299.99 on Amazon, genuinely), Bellamy was instead smiling and shaking O’Neill’s hand in front of the cameras at Parkhead.

O’Neill’s reaction was an interesting mixture of glee and subtle psychological pressure (exerted on the board, Bellamy, both?) aimed at ensuring the loan deal was just the preamble to a long and happy stay in Glasgow for his new No. 47. With Chris Sutton and John Hartson in the autumn of their careers, and summer arrival Camara having flopped so badly his exorbitant £1.5m loan deal had already been cancelled, Celtic’s boss might just have thinking that here, six months late, was his new Larsson.

“I’m absolutely ecstatic that Craig decided to sign here until the end of the season – for a start. Whatever else is questioned about Craig Bellamy, his ability is not. He has the ability to play the very best football and has done that. I would hope by the summer time, in an ideal world, we’d be in a position to at least offer him something. The rest would be up to him.”

Martin O’Neill

Before we go praising the then board for their daring and nous in pulling off a deal that must have cost them a pretty penny in wages, it’s worth remembering how the first team had wound up in a position where the electroshock treatment Bellamy administered to it was needed so badly. These were the days when the phrase ‘biscuit tin’ was on the lips of everyone who rang Superscoreboard to gripe about the board, and although it was proto Sellik Da patter of the first order, like most enduring cliches it had some grounding in fact.

From Seville all the way through to Black Sunday (as some fans prefer to call it), Celtic signed just three senior players on permanent deals. That’s two whole years where, other than the £1.5m wasted on Camara, the 350k handed over to Motherwell for Stephen Pearson was literally the only money spent. The phrase ‘managed decline’ – infamously used by Tory chancellor Geoffrey Howe about Liverpool in the ‘80s – springs to mind, even if some form of belt-tightening was inevitable after the lavish excesses of the early O’Neill years.

“The interesting thing about that era is there was always talk of the ‘biscuit tin’, but the problem for Celtic was they hadn’t actually been using the biscuit tin – under O’Neill the biscuit tin had gone right out the window,” remembers journalist and broadcaster Hugh MacDonald. “This was a time when Dermot Desmond, Brian Quinn and Peter Lawwell were saying, ‘Wait a wee minute, we got to a European final in 2003, we’ve got really good TV revenue, the best home game revenues you can get, bla-bla-bla, and we’re still making a loss.’ So they were thinking, ‘We need to come up with a business model here’, but the fact of the matter was you couldn’t come up with a business model that suited Martin, because Martin – like most managers – just wanted more and more money to spend on players. Rightly or wrongly, Martin always liked older players, he was a man of very basic principles and never really went away from them. He might have wanted a player or players to help transition between eras, but the amount of money it would take in those days, the board just weren’t willing to do it.”

Brute force, set-piece goals and recruiting centre-backs with the physical dimensions of WWE Superstar Kane had always been on page one of the O’Neill playbook, but in seasons past those qualities had been counterbalanced against the searing pace of Bobby Petta and Didier Agathe, the craft of Lubo Moravcik, the delicate subtlety of Larsson. By 2004-05 all those nuances had gone out the window and Celtic had became like an old-school stand-up comic on their farewell tour of the working men’s clubs: cutting right to the chase with the crudest, one-dimensional material they had. Which isn’t to say it wasn’t devastatingly effective at times. It’s surely no coincidence that Hartson, fully recovered from the back injury that had plagued him the season prior, enjoyed the most prolific campaign of his career with 30 goals in all competitions, or that regular starting centre-backs Stan Varga and Bobo Balde (yeah, not exactly a cultured era of passing it out from the back, was it?) managed to score an impressive nine between them.

In fact, whilst their Champions League hopes quickly went up in smoke with zero points from the first available nine in a group of death featuring Barcelona, AC Milan and Shakhtar Donetsk, domestically Celtic’s start was up there with anything previously seen under O’Neill; winning eight of their first nine games and scoring a bundle of goals, including four past Kilmarnock and Livingston and eight past Falkirk in the League Cup. The champions also continued their remarkable hot streak against Rangers, Alan Thompson’s late screamer down below the Jock Stein Stand securing a seventh consecutive derby win. Just how old and frail can they have been? After all, wasn’t this the same squad that had just put up arguably the most complete season of the O’Neill era in 2003-04, whitewashing Rangers, punting Barca out the UEFA Cup and stringing together a record-breaking 25 consecutive SPL victories?

Look carefully at the 2004-05 squad list and they’re really not as old as we tend to remember them being. Sutton was 31, Thompson was 30, while Hartson, Balde, Agathe and others were still in their late 20s. The issue was miles on the clocks, however, rather than age. The main protagonists had been playing somewhere between 40 and 60 games a season, every season, for five years, and the fact so many of their careers would quietly peter out within a year or two of leaving Celtic is telling.

“The manager had a lot of miles on the clock too,” MacDonald points out. “He’d been through all the ups and downs and was in a difficult personal situation (his wife Geraldine’s illness) which must have been really draining as well.”

O’Neill wasn’t afraid to give young players a chance, and the club had a particularly promising batch of them on its books at the time. Aiden McGeady, David Marshall and Ross Wallace all made over 20 appearances that season, Pearson, Craig Beattie and Stephen McManus chipped in here and there and the likes of Shaun Maloney and John Kennedy would have too if not for injury. The problem, perhaps, was the yawning demographic chasm running down the centre of the squad, separating these hopefuls in their teens and early 20s from the veterans in their late 20s and early 30s. Everyone seemed either to have not entered their peak years yet, or come out the other side of them, with 25-year-old Stan Petrov the only one occupying that sweet spot in the middle.

The first crack appeared with a 3-2 loss at home to Aberdeen in late October. Celtic rallied with wins over Motherwell, Shakhtar and Killie, but then came those two Ibrox losses in 10 days. The second, a 2-0 league defeat, burns a little brighter in the memory due to the red cards shown to Thompson and Sutton, the abuse doled out to Neil Lennon and O’Neill’s defiant gesture of taking Lennon to the away end after full-time. But the first, a 2-1 defeat after extra time in the CIS Cup quarter-finals, was the more alarming of the two, as Celtic were simply outran and outplayed for almost all of the 120 minutes. Their first derby defeat in almost two years, it was also their first away reverse in any domestic competition since the previous December.

This was not exactly a legendary Rangers side, as evidenced by the fact people like Steven Thompson, Hamed Namouchi and Bob Malcolm all saw regular gametime. But they were desperate to make up for their abject failure to lay a glove on Celtic the previous season, and like Pippo Inzaghi – who had broke Celtic’s hearts with a last-minute winner at San Siro that September – they had an annoying habit of simply being in the right place at the right time to capitalise on all their arch rivals’ slip ups that term.

By the time Bellamy arrived a few months later, Celtic were top – just – and had taken revenge by dumping Rangers out the Scottish Cup. But his debut was to prove a crushing anti-climax, as the Celts suffered their third derby defeat of the season (a record for the O’Neill era), this time at home in the league. A nothing game which the hosts if anyone had shaded, it suddenly veered out of Celtic’s control in the last 20 minutes when Rab Douglas had one of his semi-regular wobblies, throwing Gregory Vignal’s speculative long-ranger into the net then being lobbed by Nacho Novo. Bellamy did little other than aim a few tame shots straight at Rangers’ mulleted stand-in ‘keeper Ronald Waterreus – pretty underwhelming stuff from the guy who was meant to be the season’s saviour.

But it wouldn’t take long for his quality to emerge. The former Coventry City forward scored the last in a 5-0 Scottish Cup rout of Clyde the following weekend, and a few weeks later he was being described as ‘unplayable’ and ‘fantastic’ by O’Neill after putting the seal on a 3-1 win away to Tony Mowbray’s outstanding young Hibernian side, darting in behind the Hibs defence and nimbly skipping past the ‘keeper.

But what was he getting up to off the pitch? This is the notorious bad boy Craig Bellamy, right, joining Celtic at a time when the squad wasn’t short on big characters who loved a randan in the city centre or up the west end? There might as well have been a ‘0 days since last boozy tabloid scandal’ sign on the dressing room door at times. But unless the club media department were just doing a good job of keeping his hijinks out the papers, Bellamy appeared to be remarkably well-behaved during his brief stay in Glasgow, knuckling down on the pitch and spending more time with the coaches than his teammates off it, in scenes which seem almost reminiscent of the backroom at Satriale’s Pork Store…

“I’d stick around the training ground in the afternoons and do weights then play pool with Robbo (John Robertson) and (Steve) Walford, even though they chain-smoked all day, which wasn’t great for my asthma,” he later wrote in autobiography GoodFella. “If they weren’t playing pool they watched the History Channel. They were obsessed with criminals and fascinated by mass murderers. They shared that hobby with Martin who used to go to court to watch cases unfold sometimes. He was fascinated by the JFK assassination and James Hanratty.”

Like many Celtic players from that era Bellamy was both confused and awestruck by O’Neill; confused because the future Republic of Ireland boss wasn’t there half the time and had so little tactical instruction to pass on, awestruck because of the fraternity and winning culture he nonetheless managed to create around Barrowfield.

“I knew there was an aura about him and something that made players want to play for him. He would go and buy big defenders who could attack the ball – it was that simple. He had uncomplicated instructions. Make sure you are first to the ball in our box and in theirs, let the good players play. Usually, he turned up on the Thursday or Friday before a weekend game, like Brian Clough did at Nottingham Forest.”

“He gave some of the biggest rollickings I had ever seen. But when you played well you felt brilliant because he told you how good you were. And he told you in front of everyone so that everyone else could hear. He made you feel like you were the best player in the world. The spirit he fostered at the club was the best I’ve ever seen.”

In mid-March Bellamy scored the opener up in Inverness, then won the penalty from which Thompson sealed a vital win at a ground where Celtic often seemed to suffer costly defeats in the 2000s.

“Whatever I need to do to make Celtic want to sign me and be able to, I’ll try to do it,” he told the Celtic View afterwards. “We will cross that bridge when we come to it, but I certainly hope the club will at least want me at the end of the season.

“It has been a tough time in a lot of respects because of everything that’s happened off the field and the treatment I have had from the media and certain people who’ve never even met me. But this is a chapter of my career that, now I have got my head round what happened at Newcastle, I’m really relishing.”

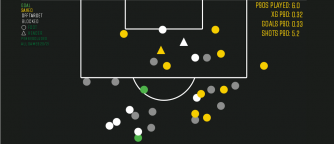

It certainly looked like it at Tannadice three days later, in what proved the No. 47’s definitive performance in a green and white shirt. Dundee United were bottom of the league and working under an interim manager, but gave O’Neill’s side a scare with goals from Jim McIntyre and future Celt Barry Robson. Victory was only assured thanks to one of the finest hat-tricks a Celtic player has ever scored. Bellamy came off the right wing and flashed a right foot shot into the top left corner in the fifth minute, then switched wings to produce almost a mirror image half an hour later: left foot, top right corner. Then, with the score at 2-2 and only 10 minutes remaining, he chested down a Sutton flick on and calmly sent a half-volley into the small gap between United ‘keeper Tony Bullock and the post. On all three occasions the ball seemed to fly into the net before the United defenders had even registered what was happening, the Welshman’s speed of thought and action frightening.

“All the goals were difficult, but they were consummated with an ease that is breath-taking,” MacDonald reflects. “You look at them again and ask, ‘Was any part of that easy?’ And the answer’s no. He was lightning quick and would fade it into the bottom corner from a wide position, as if he had this terrific 9-iron that he could just manufacture goals with. It was clear that this guy was an elite player, a top six Premier League player, easily, that was his level. He certainly gave an adrenaline injection to that team, which was really on its last legs.”

By this point the issue of Bellamy’s future was dominating every post-game press conference. And O’Neill was still showing no inclination to play things down or temper expectations.

“I am sure he will not be short of offers at the end of the season, but we’ll just have to find the money,” he remarked that day at Tannadice.

Meanwhile Bellamy himself was already fixating on the season’s last remaining derby, to be played just over a month later at Ibrox. “I’m desperate, especially after the let-down from the first game. I want to make a mark in Scotland and people say you get judged on Old Firm games, so you will have to watch me in the Ibrox game.”

Before then, Celtic’s dodgy home form struck again when they lost 2-0 to Hearts, a result quickly avenged with a 2-1 win in the Scottish Cup semis the following week, Bellamy netting the second with a deflected shot that bobbled past a young Craig Gordon. The week before their visit to Ibrox, O’Neill’s side got themselves into another Parkhead fankle, conceding two to Aberdeen inside the opening 14 minutes. A trademark booming Varga header and a close-range Hartson finish made it 2-2, and then in the 57th minute Thompson sent in a corner from the left side. In what looked like a pre-rehearsed routine, the ball flew over the entire scrum of attackers and defenders in the six-yard box and fell to Bellamy, all alone on the far right-hand side at an angle. For some reason this goal isn’t discussed as much of some of his others for Celtic, but it’s probably the best of the lot. Uncharacteristically for Thompson, the delivery was perhaps slightly overhit, meaning Bellamy had to backtrack rapidly, keeping his eye on the ball all the while and maintaining his body shape before spanking a volley off the laces – accompanied, like all the best volleys, by a satisfying ‘thump’ sound effect when you watch the footage – clean into the top left corner. Celtic held on to the three points, meaning victory at Ibrox the following weekend would give them a seemingly unassailable (sigh) five-point lead with four games remaining.

What followed was a classic of the genre when it comes to old-school derbies, full of late tackles, aggro and comically chaotic goalmouth scrambles, played in blistering spring sunshine amid an absolute din of an atmosphere. Plenty of new signings had shrunk when exposed to the unique demands of that fixture over the years, but Bellamy was in his element, squaring up to Sotirios Kyrgiakos three minutes in and mouthing what very much looked like ‘fucking prick’ at someone else as he walked off at half-time. In between these two incidents, he had scored the brilliant individual goal that would prove the winner. Petrov had already put Celtic ahead with a brave header from an Agathe cross when Thompson sparked a counter with a floated pass into the left channel. Bellamy gathered it and advanced infield, only Kyrgiakos standing between him and Waterreus’ goal. Watching this incident back is a bit like watching a cheetah bearing down on a wounded wildebeest in a documentary; the little legs whirring effortlessly, the big legs lumbering desperately, while everyone watching begins to grasp the brutal reality of what’s about to happen. Bellamy jinked away from the Greek defender and whipped a low shot into the far corner, then celebrated like a man overwhelmed, raising his hands to his face and falling to his knees over by the corner flag.

Luckily for Kyrgiakos and Rangers, he then went off with a hamstring strain early in the second half. This didn’t stop O’Neill’s men running out 2-1 winners, but make no mistake – it was a disaster. Without their talisman, all of their good work that day at Ibrox was undone at Celtic Park the very next weekend, ironically thanks to a past Celtic icon and a future one. With Sutton and Agathe also missing, Celtic were made to look utterly geriatric by Mowbray’s Hibs, deservedly losing 3-1, the coup de grace an elegant chip scored by a spiky-haired young attacking midfielder by the name of Scott Brown.

I’ll spare you a detailed reappraisal of the misery that unfolded three weeks later. Bellamy had returned for the win at Hearts on the penultimate matchday, but on the final day at Fir Park was just as strangely subdued and powerless to avert the disaster as all his teammates. The photo of him sitting bereft on the turf with his knees drawn up and mud splattered over his socks and silver boots remains one of the defining images of the event.

Six days later he put those boots to better use, looking like the Silver Surfer as he blazed up and down the wings at Hampden, petrifying the Dundee United defenders and winning both the free kick that Thompson scored his deflected winner from and the penalty Sutton skewed over the bar late on. In truth, this was one of the most drearily uneventful of all Celtic’s 40 Scottish Cup final victories, but for O’Neill and Bellamy, the pair whose bromance had been at the heart of that team’s brave but doomed last stand, it still mattered. Never again would they chew over their favourite cold case murders – the season was over, and so was their Celtic careers.

“This means a hell of a lot,” said the striker. “The way last Sunday went, it was so hard to take.”

When asked the inevitable question about his future, he simply replied, “I don’t know what’s happening, do I?”, but that July he signed for Blackburn Rovers, where he enjoyed the most prolific Premier League season of his career before being snapped up by Rafa Benitez’s Liverpool a year later.

“I really didn’t want it to end, and if I would have signed, they would have loved me,” Bellamy told The Central Club podcast back in October this year. “But it didn’t happen due to circumstances with money at Celtic at the time, and they tried everything for me to stay, but it just wasn’t possible because they could only do it on a loan. But I done it, I done that derby, and even when I watch it on telly now, I’m like…‘I was there.’”

Meanwhile Celtic revamped their squad and transitioned into the Gordon Strachan era; a period of domestic success and breaking new ground in the Champions League, but one when the striking talent tended to be a lot more workmanlike than what had preceded it.

“Celtic had fought back under Martin and spent big money, signing Sutton after one bad season at Chelsea was the equivalent of signing Timo Werner nowadays, but what had to happen eventually was financial sanity,” notes MacDonald. “Helicopter Sunday and the Bellamy situation are emblematic of that sanity – you get a top-class player in and he revitalises the team, but then he moves on, because he has to move on – you can’t pay his wages. You move into the Strachan era, and after that elite quality of Larsson, Hartson, Sutton and Bellamy, suddenly it’s Chris Killen and Scott McDonald.”

Those six tumultuous days at the end of May 2005 represented the end of the O’Neill era, with the manager and so many of his trusted lieutenants moving on that summer. But with hindsight we can see that they also represented the end of the ‘celebrity striker’ era at Celtic – the last time the club were big enough and rich enough to attract – and hold onto – household names to lead their forward line. Since then market forces have forced the club to speculate, and fortunately many of their punts have paid off, from Hooper through to Edouard and Furuhashi. But, arguably, there has never again been someone quite like Bellamy: an established star with a rare set of attributes, at the absolute peak of his powers. There will never be a positive spin to put on May 22 2005, but for those of us who lived through that season, the good memories don’t deserve to be completely photobombed by the bad.

“A deadly finisher, technically excellent, always penetrating in the final third – he was a player people just loved to watch,” MacDonald concludes. “At Celtic the impression he made was in an inverse ratio to his achievements, because of course he was part of the collapse at the end of the season. He only played about a dozen games, and he got seven goals in the league, so it’s maybe not a career-defining statistic. But it speaks to his brilliance that off the top of my head I can easily remember four of them. If anyone nowadays want to know how good Bellamy was for Celtic, go onto YouTube and look at four goals. His hat-trick against Dundee United, and his goal against Rangers at Ibrox. The prosecution rests.”